Nuclear weapons are terrifying. The sheer destructive capacity of these inventions has the potential to wipe out humanity and cause devastation to the Earth's biosphere. Yet, paradoxically, nuclear weapons could also be one of the most important causes of peace among the world's great powers since World War 2. Could it be that nuclear weapons generate more peace than they do destruction?

Nukes as Agents of Peace?

The rise of the world's two superpowers - The United States and the Soviet Union - following World War 2 prompted various academic and military scholars to think about the implications of a nuclear exchange. What would the implications of a nucelar war be? Given that nuclear weapons yield much more destructive capacity than conventional weapons, it limits their practical use given that the outcomes of such exchanges are much more unpredictable. This was especially true if the US or the Soviet Union's were to attack one another. How could the initator of a first strike not expect to be destroyed in the process? Central to the logic here is that if one party attacked the other, it could expect a full retaliation - often adressed as the policy of mutually assured destruction (or just MAD). However, to ensure retaliation in case of a first strike, the two superpowers spent a lot of time preparing and planing a credible relalitary response if their primary nuclear weapons would be taken out following a surprise first strike. This resulted in the advent of nuclear weapons carrying submarines and airplanes that were eqipped to deliver a second strike in the case of an unexpeced first strike by the adversary. Given the almost dichotomous outcome of such an exchange (destruction or non-destruction), scholars started to point out that states with nuclear weapons established a strong kind of mutual deterrence that limited their options in conflict.

Kenneth Waltz (1990), in his much-cited article Nuclear Myths and Political Realities, argued that the logic of deterrence has made nuclear weapons one of the most potent forces of peace following World War 2 by keeping the nuclear powers at bay through heightening the costs of escalating conventional warfare. Waltz suggested that it is the simplicity of the consequences of a nuclear exchange that makes it so unappealing for policy-makers, as any outcome of a nuclear exchange would result in a net-negative result. In Waltz' words:

"Anyone - a political leader or man in the street - can see that catastrophe lurks if events spiral out of control and nuclear warheads begin to fly. The problem of credibility of deterrence, a big worry in a [world with convential weapons], disappears in a nuclear one." (Waltz, 1990, p. 734)

Following the same logic, Waltz controversially suggest that "more may be better," meaning that spreading nuclear weapons would make the world a more peaceful place by establishing deterrence among the states possessing such weapons. (Waltz, 1981; 2012).

Waltz also argued that historically the initiation of wars was primarily the act of strong and powerful states, but that most contemporary wars (as of 1990) were initiated by (and conducted between) poor and weak states, suggesting that nuclear weapons might help explain this condition.

Reasons to be Sceptical

However, while the parsimonious logic of deterrence might keep rational actors from initating a costly nuclear war, it does not take into account the irrationality of some actors such as organizations, nor the possibility of accidents and miscalculation.

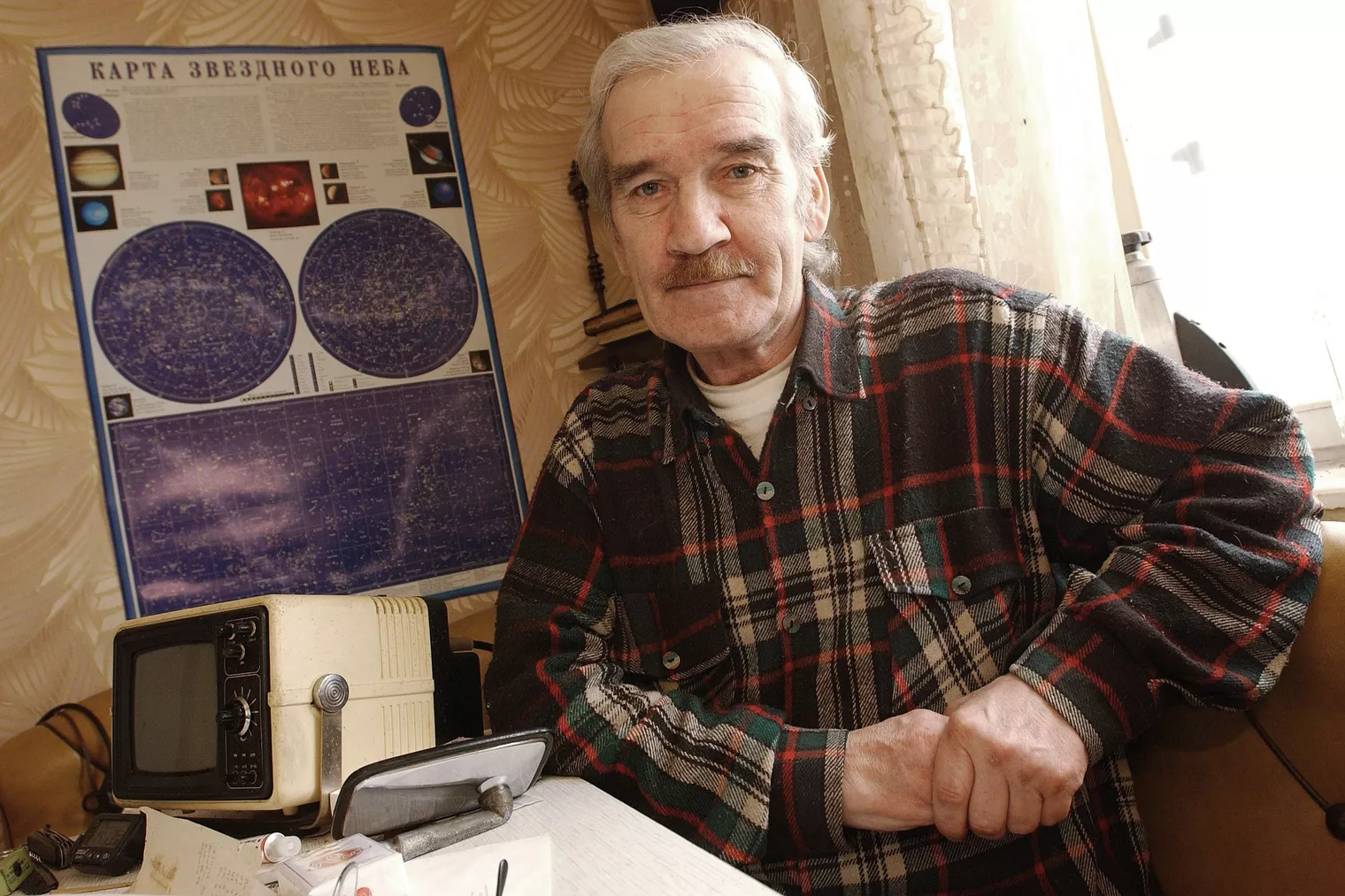

Scott Sagan (1994) suggests that military organizational structures are more suceptible to deterrence failure as these structures actively contemplate the praticalities and strategies of nuclear warfare. Sagen also points out that there is serious voliatility related to the organizational structures of new nuclear actors, as they do not have the appropriate chain of command structures or technology to safely maintain and secure their weapons. Moreover, Sagan points out that we have experienced many near-nucelar weapons accidents as well as oppurtunities for miscalculation, and that given enough time, the statistial probability for such an accident is high. Famously, in 1983, the Soviet officer Stanislav Petrov prevented an accidental nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union by detecting an error in the early missile warning system of the Soviet Union. The missile warning system that had alterted Petrov of an incoming missile attack from the US was an error, but standard operating procedures would have him prepare the launch of retaliatory Soviet missiles. In later interviews Petrov pointed out that he understood the consequences of mistakenly interpreting the detected missiles as a real strike: "If I made a mistake here, I knew I would never be able to make up for it."

Others, like Nina Tannenwald (1999; 2007), has pointed out that deterrence is not the only plausible reason for the non-use of nucelar weapons following World War 2. Tannenwald finds evidence for a prohibitive taboo against the use of nuclear weapons since World War II. She points to various empirical anomalies in which a nuclear-armed state has been attacked by a non-nuclear adversary (for example the Korean War and the Falklands War) and still decided not to use its nuclear advantage even though it would have been in its strategic interest. Indeed, if Tannenwald's hypothesis holds, then perhaps the use of nuclear weapons will never be considered in a non-existential war due the moral implications of its use.

The Problem of Studying Nukes Empirically

There are various problems with the emperical study of nuclear weapons and war. Firstly, most scientific studies of social phenomena relies on observations, and there is only one observed case of nuclear war in human history - the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War 2. To draw valid inferences, social scientists usually need more observations for cross-case comparison (a lack of observations is often referred to as the small-N problem). It is, however, fair to conclude that it is a good thing that we do not have more cases of nuclear war to base our studies on.

Gartzke & Kroenig (2016) also point out that studying the effects of nuclear weapons is prone to endogeneity, namly that the explanatory variable is correlated with the error term. Is it the actions of other states that cause one state to develop nuclear weapons, or does the development of nuclear weapons cause others to develop new capabilities? Moreover, does deterrence work because of nuclear weapons or is it because of the large and powerful conventional forces that nuclear states usually possess? Given the myriad of exogenous variables that could influence the outcome, the study of nuclear weapons certainly encourages humility.

Lastly, social scientists studying nuclear weapons are faced with a difficult information environment as many of the documents outlining nuclear strategy, numbers and accidents remain classified and unavailible to the public.

The Future of Nuclear Weapons

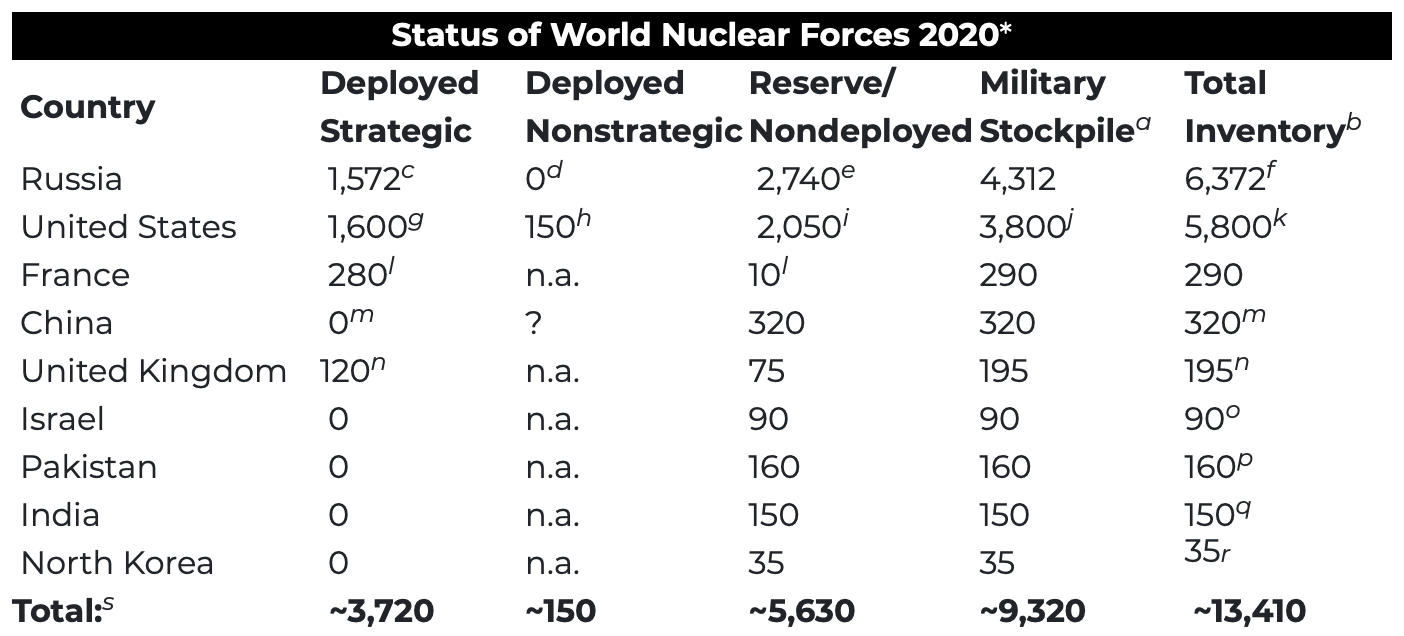

According to Kristensen, Korda & Norris (2020), there are about 13'720 nuclear warheads in existence as of early-2020. Out of these, 3'720 warheads are deployed with operational military forces today, of which about 1'800 are on high-alert, ready to be used on short notice.

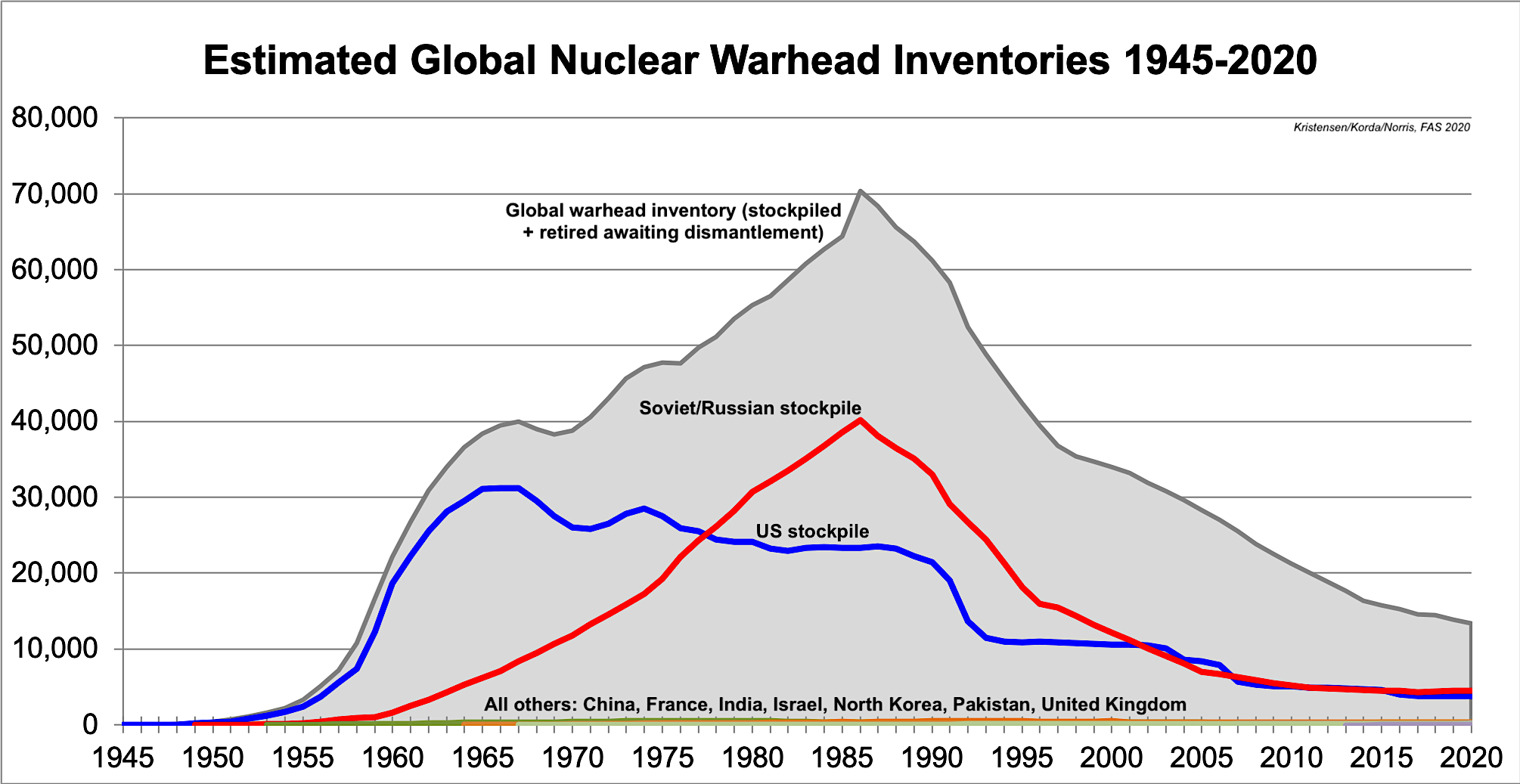

The vast majority of the world's nuclear weapons are either owned by Russia or the United States (about 91%). While the trend in absolute numbers has seen a steady decline since the end of the Cold War (down from a peak of 70'300 warheads in 1986), all the nuclear weapons states continue to modernize and update their remaining nuclear forces.

It is worth asking what we should do with the world's current arsenal of nuclear weapons? Would an ideal world be free of nuclear weapons? Perhaps yes, but according to Waltz (1990) it might highten the probabilities of conventional warfare between large and powerful states. Considering the arguments of Sagan (1996), an overall reduction in total warheads would be good as it would lower the probabilities of accidents and miscalculation. Moreover, civilian oversight over nuclear weapons use would also decrease the chance of risk-taking military elites encouraging the use of such weapons in conflict. Both Sagan and Waltz would probably agree that the logic of detterence is stable even with a low number of total warheads, as the capacity of destruction would still be very significant. A possible contemporary example of this is North Korea, whose limited nuclear arsenal still signficantly alters the balance of power vis-á-vis the United States and South Korea.

In line with Tannenwald's (2007) observations, there are various initiatives in place to reduce the numbers of nuclear weapons in existence through normative change. Recently, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) recieved the Nobel Peace Price for their work on pushing a resolution on the ban of nuclear weapons through the United Nations General Assembly with a majority in 2017. Given the growing normative stigma of these weapons, the future might yield more such international agreements, further strengthening the normative taboo of nuclear weapons use.